The following is a guest post from Matt Wald, senior communications advisor at NEI. Follow Matt on Twitter at @MattLWald.

From the batteries in our cell phones to the clothes on our backs, "nanomaterials" that are designed molecule by molecule are working their way into our economy and our lives. Now there’s some promising work on new materials for nuclear reactors.

Reactors are a tough environment. The sub atomic particles that sustain the chain reaction, neutrons, are great for splitting additional uranium atoms, but not all of them hit a uranium atom; some of them end up in various metal components of the reactor. The metal is usually a crystalline structure, meaning it is as orderly as a ladder or a sheet of graph paper, but the neutrons rearrange the atoms, leaving some infinitesimal voids in the structure and some areas of extra density. The components literally grow, getting longer and thicker. The phenomenon is well understood and designers compensate for it with a variety of techniques. One simple one is replacing some metal parts every few years.

But materials scientists at the Nebraska Center for Energy Sciences Research, at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, are working on a variety of “radiation-tolerant” materials that are self-healing. These would improve the durability of the metal parts, which would be helpful for the current fleet and more important for advanced reactors still in the design phase. Fuel elements in existing reactors are replaced after a few years, but some of the new designs would leave metal parts in place for far longer. And better materials can improve the reliability of any industry.

The researchers are working with the fact that a different class of materials, called “amorphous materials,” do not suffer damage when bombarded with neutrons. Amorphous materials, which are already in common use, do not suffer the same kind of damage. The atoms in an amorphous material are not arranged in a repeated pattern. Polymers and gels are two kinds of amorphous solids.

What the Nebraska researchers have discovered, in work partly funded by the Nebraska Public Power District and the Department of Energy's office of Nuclear Energy, is that if crystalline materials are sandwiched with amorphous materials, the flaws in the crystalline materials --- both the voids and the areas with extra density --- migrate toward the border of the two. And when they meet, they annihilate each other.

The researchers use a particle accelerator rather than a reactor, to create the damage, and then study it with powerful microscopes. They work with layers a few microns thick.

Bai Cui, an assistant professor of mechanical and materials engineering, said that at the boundary, the two flaws neutralize each other quickly. The atoms are vibrating at a rate of about 130 trillion times per second (ten to the 13th), and the flaws locate each other in about 100 cycles – that is, on the order of a trillionth of a second.

Jian Wang, an associate professor at the center, pointed out that some advanced reactor designs would have operating temperatures of over 200 degrees C and would use corrosive coolants, like molten salt or supercritical water, and are intended to run for 80 years or more. Micro-layers of amorphous materials could work well in that environment, he said.

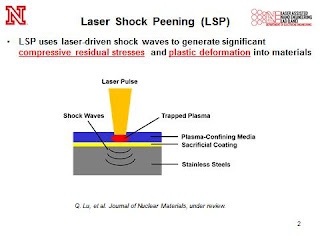

The center is also working on nano-materials that can be mixed into steel to attract and neutralize flaws. The material can be used in a weld, and is then mixed in using “laser peening.” Generally, peening means shooting particles at a target at high velocity, often to strip off the top layer of the target. But in laser peening, the pressure of light distributes the nano-materials within the steel.

The center is directed by Dr. Michael Nastasi, a research scientist formerly at the Energy Department’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. The cutting-edge nuclear research here is not its only focus; this being Nebraska, it also conducts research on wind turbines, biofuels, crop irrigation and other areas.

From the batteries in our cell phones to the clothes on our backs, "nanomaterials" that are designed molecule by molecule are working their way into our economy and our lives. Now there’s some promising work on new materials for nuclear reactors.

Reactors are a tough environment. The sub atomic particles that sustain the chain reaction, neutrons, are great for splitting additional uranium atoms, but not all of them hit a uranium atom; some of them end up in various metal components of the reactor. The metal is usually a crystalline structure, meaning it is as orderly as a ladder or a sheet of graph paper, but the neutrons rearrange the atoms, leaving some infinitesimal voids in the structure and some areas of extra density. The components literally grow, getting longer and thicker. The phenomenon is well understood and designers compensate for it with a variety of techniques. One simple one is replacing some metal parts every few years.

But materials scientists at the Nebraska Center for Energy Sciences Research, at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, are working on a variety of “radiation-tolerant” materials that are self-healing. These would improve the durability of the metal parts, which would be helpful for the current fleet and more important for advanced reactors still in the design phase. Fuel elements in existing reactors are replaced after a few years, but some of the new designs would leave metal parts in place for far longer. And better materials can improve the reliability of any industry.

The researchers are working with the fact that a different class of materials, called “amorphous materials,” do not suffer damage when bombarded with neutrons. Amorphous materials, which are already in common use, do not suffer the same kind of damage. The atoms in an amorphous material are not arranged in a repeated pattern. Polymers and gels are two kinds of amorphous solids.

What the Nebraska researchers have discovered, in work partly funded by the Nebraska Public Power District and the Department of Energy's office of Nuclear Energy, is that if crystalline materials are sandwiched with amorphous materials, the flaws in the crystalline materials --- both the voids and the areas with extra density --- migrate toward the border of the two. And when they meet, they annihilate each other.

The researchers use a particle accelerator rather than a reactor, to create the damage, and then study it with powerful microscopes. They work with layers a few microns thick.

Bai Cui, an assistant professor of mechanical and materials engineering, said that at the boundary, the two flaws neutralize each other quickly. The atoms are vibrating at a rate of about 130 trillion times per second (ten to the 13th), and the flaws locate each other in about 100 cycles – that is, on the order of a trillionth of a second.

Jian Wang, an associate professor at the center, pointed out that some advanced reactor designs would have operating temperatures of over 200 degrees C and would use corrosive coolants, like molten salt or supercritical water, and are intended to run for 80 years or more. Micro-layers of amorphous materials could work well in that environment, he said.

The center is also working on nano-materials that can be mixed into steel to attract and neutralize flaws. The material can be used in a weld, and is then mixed in using “laser peening.” Generally, peening means shooting particles at a target at high velocity, often to strip off the top layer of the target. But in laser peening, the pressure of light distributes the nano-materials within the steel.

The center is directed by Dr. Michael Nastasi, a research scientist formerly at the Energy Department’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. The cutting-edge nuclear research here is not its only focus; this being Nebraska, it also conducts research on wind turbines, biofuels, crop irrigation and other areas.

Comments