Some, if truth also informs your passion.

I was reading a press release the other day about a group that wants to motivate its members take action to push renewable energy to the policy forefront. Nothing wrong with that, of course, but the release had a lot of fervent writing that led it astray. For example:

More than eight out of 10 Americans (83 percent) – including 69 percent of Republicans, 84 percent of Independents, and 95 percent of Democrats -- agree with the following statement: “The time is now for a new, grassroots-driven politics to realize a renewable energy future. Congress is debating large public investments in energy and we need to take action to ensure that our taxpayer dollars support renewable energy-- one that protects public health, promotes energy independence and the economic well being of all Americans.”

That’s a lot of Democrats! First, I doubt any pollster ever asked this question because, second, the statement has too many moving parts. You could easily agree with, oh, 75 percent of it, but how would a pollster score that? Third, it tries to shame a respondent into saying yes. Who doesn’t want to protect public health?

Let’s try one more:

More than three out of four Americans (77 percent) – including 70 percent of Republicans, 76 percent of Independents, and 85 percent of Democrats -- believe that “the energy industry's extensive and well-financed public relations, campaign contributions and lobbying machine is a major barrier to moving beyond business as usual when it comes to America’s energy policy.”

I’m sure AWEA (the wind energy association) and SEIA (ditto solar) will be amused to read this, not to mention all the energy concerns that have renewable energy in their portfolios. Their lobbying “machines” – and those of many environmental groups – certainly like to get their views in front of lawmakers’ eyes – and have considerable success in doing so.

It’s convenient to pretend that you’re not doing what your perceived opponents are doing – if you fervently believe in what you’re doing – but you risk sacrificing your claim to the high ground. If you are doing exactly the same thing and let the truth slide away from you, you’ve already ceded it.

There can be a considerable downside to fervency. In the advocacy sphere, it is an effusion of how strongly one feels about one’s own views – and that’s great – but when it guides policy, it can seem both naïve and overheated. And not very effective.

The pull-outs come from the Environmental Working Group, but I mean it as an example rather than any particular comment on their doings. You can read the whole thing here.

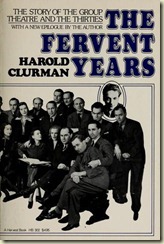

The Fervent Years is about the Group Theater, which produced a number of highly socially engaged plays during the 1930s and introduced a number of figures who would be key shapers of the American theatrical scene for decades afterward – Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets, Lee Strasburg and the author of the book, Harold Clurman. Highly recommended for fans of theater.

Comments