NEI has a new fact sheet available describing how US BWRs have improved their designs to enhance safety over the past 30 years.

Here are some good nuggets from the fact sheet:

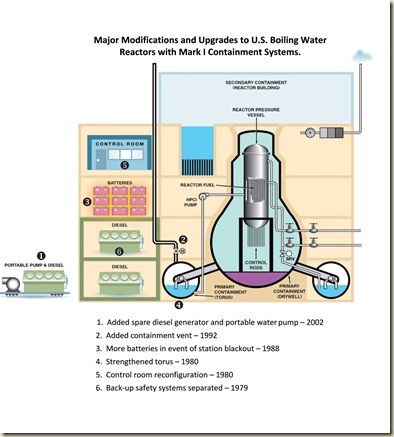

As shown above, major reactor design modifications have resulted from safety studies and analyses of past events by the NRC and the nuclear power industry. For example, as a result of the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island, the industry learned valuable lessons, including the importance of control room process and design. In 1980, access to control rooms was limited and safety alarms were given greater prominence.

Also in the early 1980s, the part of the BWR containment system known as a torus – a large, circular suppression pool sitting below the reactor – was reinforced to better dissipate pressure and strengthened to accommodate additional force. After a fire at TVA’s Browns Ferry nuclear plant, fire protection was enhanced and fire safety systems were physically separated.

The fourth modification – adding fortified vents to the containment building – was designed to prevent hydrogen accumulation inside the containment building. U.S. boiling water reactors have implemented this modification. This strengthening allows the plant to vent hydrogen from the primary containment structure via high pressure piping, precluding over‐pressurization of containment and preventing hydrogen explosions.

In 1988, enhanced battery capability was added and other emergency power upgrades were made to address the possibility of a full blackout at nuclear facilities. This gives operators more time to start backup diesel generators or restore offsite power to safety systems at the facility. In 2002, after the September 11 terrorist attacks led to an extensive review of accident scenarios beyond plant design standards, additional blackout mitigation capabilities were added as well as portable water pumps that could operate without electric power.

In addition to the redundant electrical and cooling water pumps, large backup diesel generators and other emergency electrical equipment at American plants are seismically protected and have a greater margin of safety protection from flooding, whether from hurricanes, tsunamis or river flooding. Depending on the site, flooding protection for diesel generators and emergency equipment is achieved in a variety of ways, such as watertight buildings, watertight doors and placement at high elevations. Further, whereas above ground diesel tanks at Fukushima were damaged by the tsunami, they are protected at U.S. plants by being placed underground or at higher elevations safe from floods.

In summary, U.S. nuclear power plants have significant safety measures and have undergone design modifications to protect against loss of electrical power, pressure buildup within containment and hydrogen buildup. With these added protections in place, America’s nuclear plants are well prepared to maintain safety even in the face of severe natural events.

Stop by to check out the rest of the four page document (pdf).

Comments

Reactor 6 is a later and better design than Reactors 1 through 5. The key difference is the air tight building around the emergency generator which saved the generation from destruction. Reactor 5, which is of the old design, lost it's generator but a line was run from reactor 6 to 5 saving reactor 5 from the fate of rectors 1 to 4. We know the same wave hit reactor 5 and reactor 6, but the extra protection saved reactor 6's emergency generator.

Japans root problem was not upgrading safety features of the older plants.

Better design was the difference.

The industry cannot afford not to do this, because, as fukushima shows, one particular accident anywhere will affect the public's view of all nuclear everywhere.

1) A way of getting water to fuel ponds from the plant's exterior from a normal fire hose and pump truck.

2) A light containment around the fuel pond, which could roll over the top of it, with a filtered vent.

3) Cameras with emergency battery backup, to look at the ponds.

4) Hydrogen management.

Putting a time limit like five years on the time spent fuel can stay in a pool seems like a reasonable rule. Moving the spent fuel to cask storage is something we know how to do. The cask uses passive air cooling that works even if all power is lost. Why would this not be a good rule?